Things A Little Bird Told Me Read online

For Livia

CONTENTS

Introduction: A Genius Entity

1 How Hard Can It Be?

2 Every Day’s a New Day

3 The Kings of Podcasting Abdicate

4 A Short Lesson in Constraint

5 Humans Learn to Flock

6 Happily Ever After

7 All Hail the Fail Whale

8 The Bright Spot

9 Big Changes Come in Small Packages

10 Five Hundred Million Dollars

11 Wisdom of the Masses

12 You Can Handle the Truth

13 The No-Homework Policy

14 The New Rules

15 Twenty-Five Dollars Goes a Long Way

16 A New Definition for Capitalism

17 Something New

18 The True Promise of a Connected Society

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Author biography

Acclaim for Things A Little Bird Told Me

Introduction

On October 7, 2003, a “Boston-based blogging entity” called Genius Labs announced it had been acquired by Google. The press release was picked up by various news outlets, and soon Genius Labs was added to Wikipedia’s “List of Mergers and Acquisitions by Google.” Once something makes it into Wikipedia, it is often repeated as fact. And in a way, it was fact. Genius Labs was an entity. It was me. The tale of how I got acquired—that is, hired—by Google says a lot about how I’ve made my way in the world.

A year earlier, the future wasn’t looking bright for the entity of me. My first startup, a site called Xanga that began with me and a group of my friends having the not-quite-refined idea that we wanted to “make a web company,” wasn’t what I’d hoped it would be. Tired of being broke in New York City—of all the cities to be broke in, it’s really one of the worst—I quit. My girlfriend, Livia, and I retreated to my hometown of Wellesley, Massachusetts, with tens of thousands of dollars of credit card debt in tow. We moved into the basement of my mom’s house. I had no job. I tried to sell an old copy of Photoshop on eBay (which is probably illegal), but no one bought it. At one point, I even asked for my job back at the startup—and my former colleagues said no.

The only bright spot in my so-called professional life was blogging. At the startup, we had used a piece of software from a company called Pyra, and I took an interest in the work of Pyra’s co-founder, a guy named Evan Williams. I started writing my own blog and following Evan’s, and in 1999, I was among the first to test-drive a new product Pyra had released: a web-logging tool called Blogger. To me, like lots of people, blogging was a revelation, even a revolution—a democratization of information on a whole new scale.

Xanga was a blogging community, but having left it, I was peripheral to that revolution, broke and directionless in my mom’s basement. But my blog was another story. My blog was my alter ego. Full of total, almost hallucinogenic confidence, my blog was a fictional creation. It all began with the title, inspired by an old Bugs Bunny cartoon guest-starring Wile E. Coyote. In one scene, the ultrarefined coyote says, “Permit me to introduce myself,” then presents a business card to Bugs with a flourish. It reads WILE E. COYOTE, GENIUS. By announcing himself as a genius on his business card, Wile E. Coyote epitomizes the spirit of the Silicon Valley entrepreneur. When you’re starting a company, you sometimes have nothing more than an idea. And sometimes you don’t even have the idea—just the supreme confidence that one day you will have an idea. You have to begin somewhere, so you declare yourself an entrepreneur just like Wile E. declares himself a genius. Then you make a business card and give yourself the title FOUNDER AND CEO.

I didn’t have a company . . . yet. But in the spirit of Wile E., I christened my blog Biz Stone, Genius. I made up business cards that said the same. And in my posts, I made sure to play the part. Genius Biz claimed to be building inventions with infinite resources and a world-class team of scientists at his headquarters—naturally titled Genius Labs.

One of my posts in July 2002 read, “The scale-model of a Japanese superjet that is supposed to be able to fly twice as fast as the Concorde crashed during the test flight . . . I may have to sign various paperworks that will flow millions into further development of hybrid air transit.”

Real-Life Biz was not investing in hybrid air transit. I did, however, manage to land a job as a “web specialist” at Wellesley College; Livia found a job, too. We rented a place near campus so I could walk to work. It wasn’t so much an apartment as the attic of a house, but at least it wasn’t my mother’s basement.

My alter ego, Genius Biz, meanwhile, continued to exude confidence, gaining more and more of a following. He was Buddy Love to my Professor Kelp. But as I sustained this charade, something started to happen. My posts weren’t just wacky anymore. Some of the thoughts weren’t in the character of a mad scientist; they were my own. As I continued to write about the web and think about how it might evolve, I started hitting on ideas that I would one day incorporate into my work. In September of 2003 I posted:

My RSS reader [a syndicated news feed] is set to 255 characters. Maybe 255 is a new blog standard? . . . Seems limiting but if people are going to read many blogs a day on iPods and cell phones, maybe it’s a good standard.

Little did I know how ideas like this, which seemed incidental at the time, would one day change the world. And I say this with all the humble understatement of a self-described genius.

Google acquired Evan Williams’s company, Blogger, in early 2003. In the four years it had taken for blogging to evolve from a pastime of a few geeks into a household word, Ev and I had never met or even talked on the phone. But in the interim, I had interviewed him for an online magazine called Web Review, and I still had his email address. Now I worked up the confidence to contact him. I sent him an email congratulating him on the acquisition and saying, “I’ve always thought of myself as the missing seventh member of your team. If you ever think of hiring more people, let me know.”

It turned out that, unbeknownst to me, Ev had been following my blog, too. In the tech world, that made us practically blood brothers. Though he was surrounded by some of the best engineers in the world, he needed someone who really understood social media—someone who saw that it was about people, not just technology—and he thought I was the guy.

He wrote back right away, saying, “Do you want to work here?”

I said, “Sure,” and I thought it was a done deal. I had a new job on the West Coast. Easy peasy.

I didn’t know it at the time, but behind the scenes Evan had to pull strings in order to hire me. Actually, they were more like ropes. Or cables—the kind that hold up suspension bridges. Google had a reputation for hiring only people with computer science degrees, preferably PhDs; they certainly didn’t court college dropouts like me. Finally, the powers that be at Google begrudgingly agreed that Wayne Rosing, then Google’s senior VP of engineering, would talk to me on the phone.

The day of the call, I sat in my attic apartment staring at the angular white Radio Shack phone I’d had since I was a kid. It had a cord. It was practically a collector’s item. I’d never interviewed for a job before, and nobody had prepped me for this. Although I naively assumed that I already had the job, I at least understood that talking to Wayne Rosing was a big deal for someone in my position. I was nervous that I’d mess it up, and with good cause. A few days earlier, a woman from the human resources department had called me, and I’d joked around with her. When she asked me if I had a college degree, I told her I didn’t but that I’d seen an ad on TV for where to get one. She didn’t laugh. Clearly my instincts in this department weren’t reliable. Real-Life Biz was consumed by self-doubt.

&nbs

p; The phone rang, and as I reached for it, something came over me. In that instant I decided to abandon all the failure and hopelessness I’d been carrying around. Instead, I would fully embody my alter ego: the guy who ran Genius Labs. Genius Biz was on the job.

Wayne began by asking me about my experience. I guess he’d talked to the HR woman, because his first question was why I hadn’t finished college. With utter confidence, I explained that I’d been offered a job as a book jacket designer, with the opportunity to work directly with an art director. I considered it an apprenticeship. As the interview went on, I acknowledged that my startup had been a failure—for me, at least—but explained that I’d left because the culture didn’t fit my personality. In Silicon Valley, the experience of having crashed and burned at a startup had value. I told him about a book I’d written on blogging.

Then, in the middle of his questions, I said, “Hey, Wayne, where do you live?” That took him aback. I guess it sounded a little creepy.

“Why do you want to know where I live?” he asked.

“If I decide to take this job, I’ll need to pick a good location,” I said.

Decide to take this job. I didn’t even know I was being audacious. But somehow it worked. I had the job. I was going to join Google. Evan invited me out to California to meet the team. With its seemingly limitless resources, scientists, and secret projects, Google was the place on earth most resembling my imagined Genius Labs.

A couple of years later, Ev and I would quit Google to start a company together. I had joined Google before the IPO, so I would be leaving lots of valuable shares behind. But my move to Silicon Valley wasn’t about a cozy job—it was about taking a risk, imagining a future, and reinventing myself. My first startup had failed. But my next startup was Twitter.

This book is more than a rags-to-riches tale. It’s a story about making something out of nothing, about merging your abilities with your ambitions, and about what you learn when you look at the world through a lens of infinite possibility. Plain hard work is good and important, but it is ideas that drive us, as individuals, companies, nations, and a global community. Creativity is what makes us unique, inspired, and fulfilled. This book is about how to tap into and harness the creativity in and around us all.

I’m not a genius, but I’ve always had faith in myself and, more important, in humanity. The greatest skill I possessed and developed over the years was the ability to listen to people: the nerds of Google, the disgruntled users of Twitter, my respected colleagues, and, always, my lovely wife. What that taught me, in the course of helping to found and lead Twitter for over five years, and during my time at startups before then, was that the technology that appears to change our lives is, at its core, not a miracle of invention or engineering. No matter how many machines we added to the network or how sophisticated the algorithms got, what I worked on and witnessed at Twitter was and continues to be a triumph not of technology but of humanity. I saw that there are good people everywhere. I realized that a company can build a business, do good in society, and have fun. These three goals can run alongside one another, without being dominated by the bottom line. People, given the right tools, can accomplish amazing things. We can change our lives. We can change the world.

The personal stories in this book—which come from my childhood, my career, and my life—are about opportunity, creativity, failure, empathy, altruism, vulnerability, ambition, ignorance, knowledge, relationships, respect, what I’ve learned along the way, and how I’ve come to see humanity. The insights gained from these experiences have given me a unique perspective on business and how to define success in the twenty-first century, on happiness and the human condition. That may sound pretty ambitious, but when we’re taking a break from developing hybrid air transit, we aim high here at Genius Labs. I don’t pretend to know all the answers. Actually, strike that: I just might pretend to know all the answers. What better way to get a closer look at the questions?

So, in a single phone call, Genius Biz had landed a job at Google pre-IPO. Or so he thought.

After my conversation with Wayne Rosing, I thought I would just drive to California and start my new life. In anticipation of that, my would-be employers had asked me to fly out to the Google offices in Mountain View to meet them in person and finalize the details.

At this point Evan Williams was my champion. Having never laid eyes on me, he had pushed Google to hire me, and now he was meeting me at the airport to take me to my new workplace. I had no idea what a big part of my life Evan would become, and that one day he and I would start Twitter together. At that point I was just grateful for the ride.

I arrived at the San Francisco airport on an early flight, and when Evan picked me up in his yellow Subaru, Jason Goldman, his right-hand man at Blogger, was in the passenger seat. I jumped in the backseat, and as we drove to Google, I was immediately jokey about my plane ride. As is my wont, I probably made some inappropriate remarks, because I remember Evan and Jason laughing and saying, “We just met this guy five seconds ago and this is where he’s going with his banter?” I tend to come on a little strong, but I could see that they were pleasant and casual and had a nice rapport. I wasn’t surprised. I’d been reading Evan’s blog for so many years that I knew there was a thoughtful person in there. He was wearing jeans, a T-shirt, and sunglasses. He had a slight build, a big smile, and he drove like a maniac. Goldman has a memorable laugh. He usually hits a high note at the end.

Because Google hadn’t gone public yet, it was still a startup, but it was already several years in and considered very successful. There was no Googleplex yet, just a bunch of people working in leased stucco buildings.

Evan showed me the place and introduced me to the Blogger team. After making the rounds at the office, he and I went to a party in Mountain View for a bit; then we drove up to San Francisco to have dinner at an Italian restaurant in the Marina District with his mother, who was in town, and his girlfriend. After dinner and plenty of wine, I was ready to go to my hotel—I had more meetings at Google the next day and I was still on East Coast time—but Evan had other plans for us.

“Let’s go to the Mission! I’ll show you some of my favorite bars.”

Evan, his girlfriend, and I kept the party going at a bar called Doc’s Clock. I ordered a whiskey neat, and the bartender poured me a full juice glass.

“Wow,” I said, marveling at the quantity.

“They have a good pour here,” Ev said.

By last call, at 1:40, we’d all had plenty to drink. Ev, who was blitzed, leaned back in his chair, opened his arms wide, and said, “Biz, all this could be yours.” We had a table in the rear, and I was sitting with my back to the wall. From my vantage point, I could see the whole bar, a dimly lit, hipster-friendly dive bar, not much more.

“Really?” I said sarcastically. “This?”

Evan put his head down on the table. We were done.

The next day, I had twelve meetings with various Google executives. It became immediately clear to me that these “meetings” were in fact interviews. Turned out this job I thought I already had wasn’t yet mine. I was smack in the middle of Google’s famously rigorous application process.

But I swear what got me through was the certainty that the job was mine. Channeling my Genius Labs persona wasn’t the only strategy I had up my sleeve.

Before I got on the phone with Wayne Rosing, I’d never applied for a real job before. I had no idea how an interview, phone or live, was supposed to go. But as I’ve said, I did have one thing going for me: the well-established confidence and chutzpah of Biz Stone, Genius.

Still, you can print that on a business card or type it on a website, but you can’t just summon that attitude out of thin air. So there was something I did before the phone interview that helped me summon Genius Biz. Here’s how it worked: In the days leading up to that phone call, I took the idea of working on the Blogger team at Google and let it bounce around in my head. Back then I liked to take a slow jog from my apartm

ent, which was practically on the Wellesley campus, down to Lake Waban and around the two-plus-mile dirt path. As I ran, I pictured myself in a strange office somewhere near San Francisco, with a bunch of guys I’d never met, doing the work I wanted to do.

Most of Google was entirely made up of computer science PhDs. They were very talented at building software. The role I envisioned for myself was to humanize Blogger. I would take over its home page—the company’s official blog—and make the Help area into a product called “Blogger Knowledge,” where I would highlight features of the service. I would give a voice and brand to Blogger. (Though I didn’t know it at the time, this is what I would find myself doing at every company I joined: embodying and communicating the spirit of the thing we were creating.)

This is a useful exercise with any problem or idea. Visualize what you want to see happen for yourself in the next two years. What is it? I want to have my own design studio. I want to join a startup. I want to make a cat video that goes viral on YouTube. (Can’t hurt to aim high.) As you’re working out or going for a walk, let that concept bump around in there. Don’t come up with anything specific. The goal isn’t to solve anything. If you take an idea and just hold it in your head, you unconsciously start to do things that advance you toward that goal. It kinda works. It did for me.

Now I was at those offices I had imagined. They were a little different from my fantasy; I’d expected . . . I don’t know, a Googleplex maybe, and instead there was a bunch of nondescript buildings; Blogger was in building number π—but I’d already been working for Blogger in my head for at least a week. Besides, it was hard to be intimidated when nobody seemed to understand what job they were interviewing me for. It all made sense to me and Evan, but the human resources department at Google was a little bafled by my job description. My explanation that I was going to add humanity to the product only seemed to confuse them further. In interviews, the Google staff was known to make engineers solve difficult coding problems on a whiteboard. They had no idea what to ask me. My hobbies? Adding to the general fuzziness of the interviews, Evan and I had been out ’til 3:00 or 4:00 a.m.

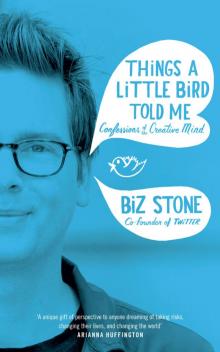

Things A Little Bird Told Me

Things A Little Bird Told Me